It was one of the most daring missions of D-Day: land by sea at dawn, climb 100-foot cliffs defended by the enemy, overwhelm the enemy, and disable their heavy artillery guns. It sounds almost mission impossible.

But the mission was accomplished – and a man from the Jersey shore led the way.

It was the mission of the U.S. Army Rangers along the coast of France and it was critical to the Allies’ success on D-Day. And that man was Leonard G. “Bud” Lomell of Point Pleasant Beach and later Toms River, New Jersey.

The Allied Plan

D-Day – June 6, 1944 – the invasion of Normandy was 75 years ago. It was the turning point of the Second World War. Success was imperative: there was no back-up plan. If the invasion had failed, the war may have gone on indefinitely, or ended in a very different – perhaps, ominous – way.

The Allied objective was simple. In orders to the soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force from the Supreme Commander, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower: “You will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed people of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.”

The goal was simple; the execution complex. It was, in British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s words, “the most difficult and complicated operation ever to take place.”

Five beaches along a 60-mile stretch on the French coast would be attacked, Hitler’s vaunted “Atlantic Wall” was to be breached, and the Allies would move inland. Two of those beaches – assigned to the Americans – code named “Omaha” and “Utah” lay in the western sector on the invasion front. Between these two beaches was a windswept promontory known as Pointe du Hoc. It was heavily defended by the Germans and fortified (so the Allies thought) by 155 mm guns which could rain devastating artillery fire on the landing beaches and ships in the English Channel. This pointe had to be taken and the guns neutralized before the landings began. If the beaches at Omaha and Utah were not successfully taken, success on D-Day would be imperiled – as the British and Canadian beaches to the east would be isolated. The counterattacking Germans would then divide and conquer and D-Day might fail.

The Army Rangers

The task of taking out the guns was assigned to America’s Army Rangers – an elite fighting force. The first Rangers unit in World War II, the First Battalion, was formed in 1942 in Northern Ireland. About 2,000 men had volunteered to join, but after vigorous testing, only 500 would form the battalion of six companies known as Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog, Easy, and Fox, or A, B, C, D, E, and F. They trained with British commandos and fought with distinction in North Africa. Eisenhower, it was said, was “sold” on the Rangers.

As a result of the First Battalion’s success, a handful of battle tested Rangers were sent back to the States to help train the newly created Second and Fifth Battalions. In 1943, the Rangers trained in Tennessee and the Second Battalion was shipped off first to Ft. Dix, New Jersey and then, later, England. Overseas, they continued training – including, importantly, the art of cliff climbing.

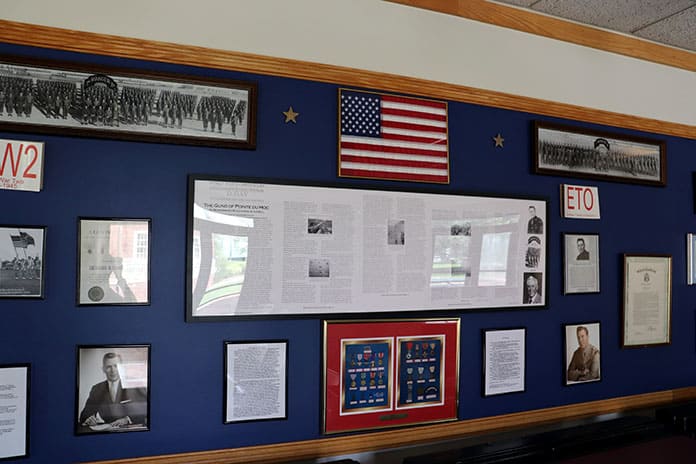

“These Are The Boys Of Pointe Du Hoc”

The Germans considered Pointe du Hoc impregnable. In the 18-mile gap from Omaha to Utah Beaches, it was located in-between and was protected from the sea by the cliffs. Inland, the land was flat and protected by barbed wire and cement fortifications. It was the Germans’ strongest held position along the invasion front.

Rangers of the Second Battalion approached by sea in landing crafts, but they went off course and were delayed by 40 critical minutes. With supporting naval gun fire ending at the assigned time of 6:30 a.m. – H-Hour – this gave the Germans time to regroup from the bombardment. Nine landing craft loaded with men landed at the cliff seawall at 7:10 a.m. In 20 minutes, which must have seemed like a lifetime, the Rangers climbed the cliffs using rocket fired ropes with grappling hooks and extension ladders. Some were able to scramble up the face of the cliff from the rubble from the naval bombardment.

Sgt. Lomell was one of the first to scale the cliffs. Lomell, a Point Pleasant Beach native, like all Rangers, was a volunteer. He had enlisted in the Army following college. He was the adopted son of immigrant parents from Scandinavia who lived in New York. They moved to the Jersey shore and the family struggled through the Depression. Three years after enlisting, he was about to participate in the greatest amphibious landing in the history of mankind. Off loaded from his landing craft, Lomell had to first swim about 20 feet to the shale beach and was slightly wounded by a machine gun bullet.

Getting up the cliff had somehow been accomplished – but the attacking force of 225 men was already reduced to about 200. Once on the flatland, the Rangers found it in utter destruction. Moonlike craters (from the bombings) and debris everywhere. Some cement structures were still intact, while others were left to rubble.

But, the artillery guns! There were no guns! Where were the guns? The Germans had cleverly placed timbers and wooden beams sticking out of their cement casemates to make it appear to aerial reconnaissance that the guns were positioned at the Pointe.

As the Rangers moved inland, they met one of their other objectives – block a coastal highway that connected Omaha and Utah Beaches. That would help impede any German counterattack along the front. But where were the guns?

After helping secure the road with some of his D Company men, Lomell and Staff Sgt. Jack Kuhn followed a path of deep tire tracks along a dirt lane – further inland. About 250 yards from the blocked highway, Lomell found the guns. “Jack, here they are. We’ve found ‘em. Here’s the God-damned guns.”

The guns, camouflaged in an apple orchard, were pointed in the direction of Utah Beach and were ready to fire. There they were – five 155 mm guns! Unbelievably, they were left un-attended, as the Germans were about 100 yards away, confused and re-organizing in the fog of war. Using his gun butt, Lomell bashed the sites on all five guns. Two guns were further disabled using silent, thermite grenades which melted the turning mechanisms. Lomell ran back to the Rangers on the roadway, got more grenades, and destroyed the remaining three guns.

The guns were rendered inoperable – mission accomplished! It was 9 a.m. It was the first successful United States’ military mission on D-Day. Of this feat, the esteemed World War II historian, Stephen Ambrose recognized Bud Lomell as the single individual – other than Dwight Eisenhower – as most responsible for the Allied success on D-Day.

But the fighting was not over for the Rangers. They were now on the defensive and had taken heavy casualties. On the afternoon of June 6th, they signaled for ammunition and reinforcements. There would be none for 48 hours. The Rangers were isolated and fought off German counter attacks. When finally relieved, they were down to a fighting force of just 50 men.

But they had gained back a toe hold of freedom. As President Reagan said at 40th anniversary ceremonies, “these are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent.”

For Bud Lomell, he would be wounded several times more in the war and receive a battlefield promotion to Second Lieutenant. More than once, he told this writer that what he experienced in taking “Hill 400” in Germany in December 1944, just before the Battle of the Bulge, was more dangerous and life threatening than D-Day. Perhaps this was Bud’s simple modesty.

One Of The Greatest Men Of The Greatest Generation

As we look back on 75 years ago:

If the 20th century was the “American century” – and it was;

And if the seminal event of that century was the Second World War – and it was;

And if the turning point of that war was D-Day, the invasion of Normandy – and it was;

And if the turning point of that invasion was the struggle at Omaha and Utah beaches – and it was;

And if that struggle depended upon military success between those beaches at a windswept coastal point – and it was;

And if what Bud Lomell did at that Pointe in disabling those guns turned the tide of battle – and it was;

Then – think about it: here was a man from the Jersey shore who stood in the middle of the 20th century, the American century, and turned history for the better – for freedom and democracy.

Bud Lomell was simply one of the greatest men of the greatest generation.

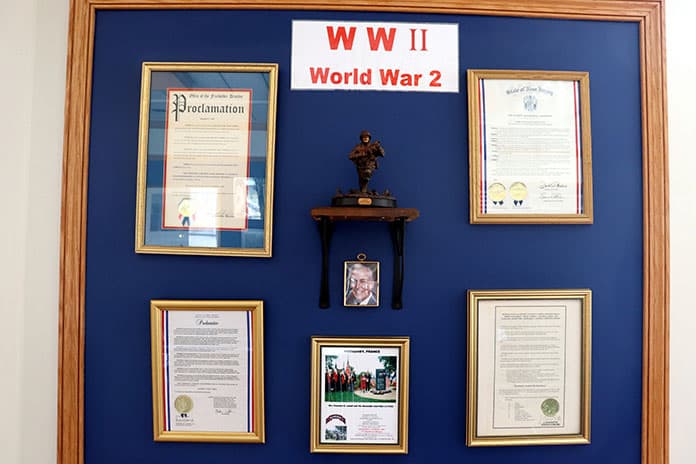

Bud has been gone now eight years. He touched many, many lives – both in war and in peace. He was a hero to many of us. For me, it was an honor to call him friend.

SOURCES: “D-Day,” by Stephen Ambrose; “The Greatest Generation,” by Tom Brokaw; “Rudder’s Rangers,” by Ronald Lane; “Rangers Lead the Way,” by Col. Thomas Taylor (ret.)

J. Mark Mutter, Esq., was a law clerk in Bud Lomell’s law firm. He has been to Normandy numerous times, including three with Bud Lomell in 1994, 1999, and 2004 for anniversary ceremonies. He is an associate member of the Descendants of World War II Rangers.