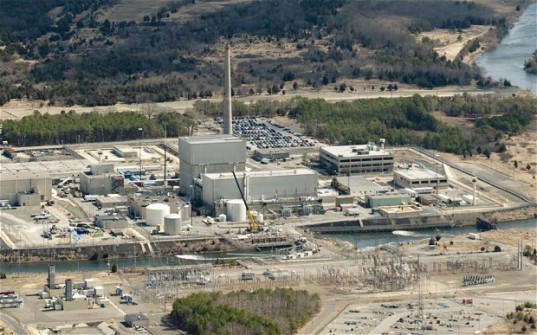

FORKED RIVER – The oldest nuclear power plant in the United States will close its doors permanently later this year.

Oyster Creek Generating Station will close in October 2018, a full 14 months before its original closing date of December 2019.

Lacey Township Mayor Nicholas Juliano said the township heard about the plans early in the day on Feb. 2, the same day the general public was notified of the change. The township has been preparing for the site’s closing for some time.

“Lacey Township has been working with other entities to bring in an alternative power source to the site,” he said. “In addition, we have been working with the office of state planning for approval on our Plan Endorsement Town Center application that will allow for more impervious coverage on our commercial ratable properties, allowing for expansion and redevelopment on many of the commercial sites along the Route 9 and Lacey Road corridor to help offset tax base loss from Oyster Creek closing.”

Juliano continued: “Long after Oyster Creek ceases to operate they will continue with a team of employees who will remain on site protecting the facility and the public with a highly skilled staff of experts to oversee the entire dismantlement process. (plant owner) Exelon will continue with its safe operation through decommissioning which could take up to 20 years with a strong environmental monitoring program. Oyster Creek’s tax base will remain intact until such time that buildings are dismantled and no longer exist on the site. As to the spent fuel, Exelon, being the current holder of the license, will be responsible for safely maintaining the on-site spent fuel storage systems. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) regulations requires licensees to manage and provide funding for the management of spent fuel as long as the spent fuel remains on site.”

Exelon Generation, the company based in Kennett Square, Pa., that owns Oyster Creek, paid $2,247,300 in taxes for the land the plant operates on in 2017, according to township records. The property also generated $11,107,588 in Energy Tax Receipts. These are taxes directly given to towns in exchange for allowing utility companies to operate there.

The station pays out $68 million in annual salaries, according to published reports. The company did not directly answer questions about what the future holds for the site, only that it would be maintained to the highest safety standards.

“For nearly a half-century, the men and women at Oyster Creek have operated our facility with safety, reliability and respect for our environment as their primary focus. That commitment will remain long after the plant shuts down and decommissioning takes place,” Exelon spokeswoman Suzanne D’Ambrosio told Micromedia Publications.

Every two years, the station enters a refueling outage: the plant shuts down and a third of the fuel assemblies used in the plant’s reactor are replaced with new ones. That would be happening this October, if the plant had remained open until next December. With the permanent shutdown, all fuel will be transferred to the used fuel pool, and the plant will be “permanently defueled,” she said.

Once that’s completed, those systems that are no longer required will be removed from service, to be dismantled or put in long-term storage.

“A fuel handler certification program and shutdown emergency plan will be put into place. Security adjustments may also be made based on the new configuration with all fuel in the pool. These actions allow for facilitating staff adjustments,” D’Ambrosio said. “The schedule and activities for decommissioning described in the Post Shutdown Decommissioning Activities Report (PSDAR) will be implemented at the site. Some workers will remain on site for the first few years after the plant is shut down to work through the process of putting the plant in a dormant condition. After that, a smaller workforce will remain at the site until the plant is decommissioned. The number of individuals needed at the site depends on decommissioning activity timing.”

Exelon employs 500 people at Oyster Creek. The company is working to place them in-house at other facilities; Exelon operates in 48 states and Canada, and has a station in Mays Landing and other locations in the Philadelphia/Camden metro area.

“I want to thank the thousands of men and women who helped operate Oyster Creek Generating Station safely for the past half-century, providing generations of New Jersey families and businesses with clean, reliable electricity,” Exelon president Bryan Hanson said in a statement. “We will offer a position elsewhere in Exelon to every employee that wishes to stay with the company, and we thank our neighbors for the privilege of allowing us to serve New Jersey for almost 50 years.”

As for providing power for those 600,000 homes Oyster Creek currently serves, D’Ambrosio told Micromedia Publications that PJM Interconnection is solely responsible in ensuring “grid reliability.” She said Exelon is confident PJM will procure the generation resources needed to cover Oyster Creek’s 600 megawatts of generation.

The station is “a single-reactor plant that produces 625 megawatts of zero-emissions energy: enough carbon-free electricity to power 600,000 homes,” according to company literature. The plant went online in 1969. A plan was reached by state officials and Exelon to close the plant by 2019.

The plant’s closing is welcome news to environmental groups across the region.

“It’s important that Oyster Creek is closing early, because it should have closed a long time ago. This is the oldest nuclear plant in the country and it’s falling apart. It leaks radioactive tritium, has problems with storage, and erosion with containment vessels, among other issues. This plant was a disaster waiting to happen so it’s vital for our coast that it’s closing early. This plant is a dinosaur and it’s good that’s its going extinct,” Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, said.