LAKEHURST – Dr. Horst Schirmer still remembers when he lifted the entire Hindenburg with his bare hands.

Schirmer’s father, Max, had been with the Zeppelin Company from 1923 to 1945. He designed a new propeller that was tested on that fateful flight. He would take his son into the hangar on weekly trips.

Schirmer’s father let him fly on it, too, once. But he remembers vividly seeing the Hindenburg at rest in the hangar, stretching 803 feet long. Following his father’s instructions, he put his hands on it.

Schirmer’s father let him fly on it, too, once. But he remembers vividly seeing the Hindenburg at rest in the hangar, stretching 803 feet long. Following his father’s instructions, he put his hands on it.

“Now, lift it up,” his father had said. Incredibly, it began to rise.

“I raised it with my hand. I couldn’t believe it! It was like a balloon,” he said.

Now 80 years later, Schirmer is still very pleased with his – and his father’s – place in airship history.

Schirmer speaks with technical knowledge of the inner workings of the airships. Indeed, his father had wanted him to study physics. He, instead, opted for medicine, against his father’s wishes.

He practiced as a urologist in Maryland. Now, at 85, he is retired from surgery, but still teaches and does cancer research at Johns Hopkins University.

He will be visiting Lakehurst this weekend as part of the Hindenburg anniversary events. His talk was scheduled for May 5th at a banquet, and for May 6th at a remembrance ceremony.

Lots of people want to discuss the disaster. The tragedy. He wanted to talk about the people. The names and faces of those behind the history.

“I knew pretty much all the crew that flew it,” he said.

Many key people made contributions to the history of lighter-than-air craft. It seemed to be a tightly-knit group. He knew many of the engineers and captains. They were friends and they were neighbors, and he went to school with their children.

“I was born in 1931. The Hindenburg was started in 1931. They finished it in 1935.” To put it in perspective, Germany was churning out two airships a month at its peak.

A man who owned 51 percent of the stock in Hindenburg put the swastika on the side as propaganda.

“A lot of people didn’t like it, suffice it to say,” he said.

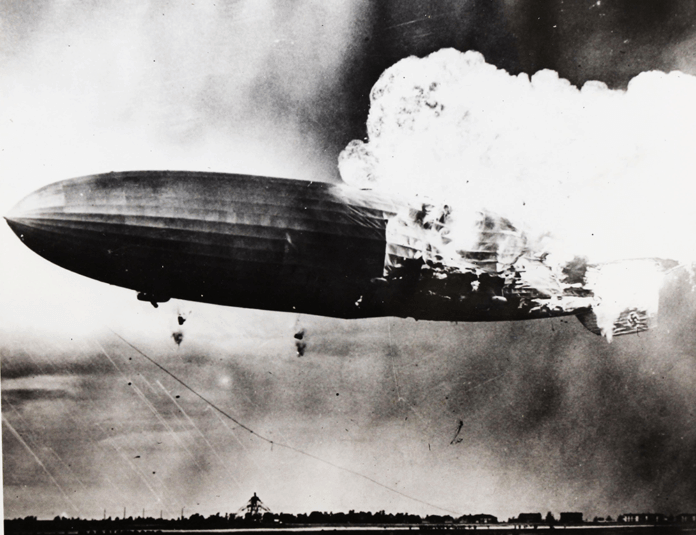

There have been many theories as to the cause of the disaster, but none of the experts have reached a consensus.

Some have suggested static electricity sparked a leak of hydrogen, but he doesn’t agree with that: “Hydrogen alone doesn’t burn. It needs oxygen.”

Lightning is another theory, but he discounts that idea: “The ship had been hit before by lightning, but nothing had happened.”

“I don’t think anybody will ever know,” he said.

Unfortunately, the Hindenburg disaster was not an isolated incident. It wasn’t even the most tragic. In comparison of sheer numbers, the Akron’s 1933 crash off of Barnegat Light claimed 73 (plus two more, when another blimp crashed on a rescue mission to recover the Akron’s survivors).