OCEAN COUNTY – As summer takes hold in Ocean County and hot weather is finally on the rise, something else is also on the rise this time of year – drug use.

The opioid epidemic is nothing new, but there are a few things that have changed, in both good and bad ways, over the past few years. There are also some things that have stayed the same. According to the Ocean County Prosecutor’s Office, so far there have been 74 drug overdose deaths in the county this year, pending a few toxicology reports, which is the exact number we were at the same time last year.

“I track it using the last two years and we’re sort of on the same pace as last year, and last year we had 209 overdose deaths,” said Prosecutor Joseph Coronato.

He said drug use and overdoses tend to pick up during the summer, and then really start to spiral out of control starting in November, as the holidays approach.

A New High

One of the problems, and the bad news, is fentanyl. He said in 2014, the packets of heroin they came across had about 10 percent fentanyl. In 2015, that number rose to 30 percent, and in 2016, it shot up to 65 percent.

“In 2017, some of the packets are totally fentanyl and not even heroin anymore,” said Coronato. “That is what I call the synthetic storm. That’s what’s really killing all these people. And that’s one reason why we’ve not been able to ‘curb the tides’ so to speak.”

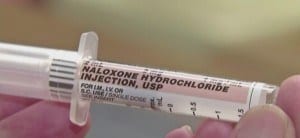

But it’s certainly not without trying. Ocean County law enforcement officers were the first in the state to use the opioid reversal spray Narcan back in 2014, after Coronato and the Prosecutor’s Office saw that heroin deaths at the end of 2013 were doubling what they were the year before.

In the first year that police officers used Narcan, the death rate dropped from 112 to 101. So far this year, Narcan has been sprayed 164 times to revive someone from an overdose.

OORP to HARP to HART

Coronato said that once officers started using Narcan, they realized they would often be spraying the same person two or three times. To combat that, OORP was born. The Opioid Overdose Recovery Program allowed a recovery coach to come out to the hospital when someone was taken to the emergency room after a Narcan overdose revival. That person could then be clinically analyzed and talked to about detox, but most importantly, have an opportunity to go into a treatment program, and ultimately save their lives. Around 50 to 60 percent of people were seizing that opportunity and getting help.

“But then it became apparent to me that the only way that we’re putting people into the program is that we almost had to overdose them and almost die,” said Coronato.

Hence, Blue HART was born.

The good news is that Blue HART – Heroin, Addiction, Recovery & Treatment, formerly known as HARP, is doing well. The program, which is now offered via the Brick, Manchester, Stafford and Lacey Police, allows drug users to turn themselves in at police headquarters and get addiction treatment without the fear of prosecution. So far, 165 people have been helped.

Coronato said the program is really about making a difference in people’s lives and treating them like human beings. He receives letters from grateful family members about how thankful they are for the program now that their loved ones are in rehab and doing well. Recovery coaches are attached to participants in the program, which will ideally lead to more success stories and give the Prosecutor’s Office an idea of what’s successful and what’s not.

Coronato said the program is really about making a difference in people’s lives and treating them like human beings. He receives letters from grateful family members about how thankful they are for the program now that their loved ones are in rehab and doing well. Recovery coaches are attached to participants in the program, which will ideally lead to more success stories and give the Prosecutor’s Office an idea of what’s successful and what’s not.

“We want to find out what they’re doing, where they are, what their status is – because what we’re interested in is in outcomes. We’re not looking to prosecute anybody, what we’re looking to do is make a difference in that person’s life.”

Expanding the program is on the horizon, but not without its challenges. Coronato said the program relies on detox beds and scholarships to stay afloat. Some people have medical insurance that pays for their treatment, but mostly it’s funded through scholarships from treatment centers that allow them to place individuals in a facility at no charge.

“I can’t have somebody coming into a police station and us not finding a bed, saying we’ll come back in two, three days – it doesn’t work that way.”

Adding to the substance abuse issues, he said often the individuals coming in for treatment may also have mental health, social, family or legal issues as well, which need to be assessed right away. So while other police departments in Ocean County are ready to hop on board, it’s not as simple as opening the floodgates.

“The biggest problem is getting detox beds and then being able to get treatment,” he said.

Lacey Joins Forces

Lacey Police is the latest department to join the Blue HART program. Chief Michael DiBella said he unofficially released the news the week of June 18 and had two people come in for help.

“I’ve been really interested since the prosecutor put this together,” said Chief DiBella, adding that decreasing the heroin epidemic in Ocean County is something he’s been passionate about since he became police chief last year.

He has seen officers throughout his police career struggle to interact with families who are dealing with a loved one using drugs because of so many unanswered questions. The same question would always come up: where do we go for treatment? There were issues with waiting lists for treatment centers or some facilities not taking insurance, or people who had tried to get their loved ones help but failed. He knew they needed to do something.

Chief DiBella said that while Lacey doesn’t have more of a drug problem than any other town, it’s about providing availability for treatment, and he hopes that this time next year, other counties and towns in New Jersey will have hopped on board and perhaps set the tone for the whole country.

“It’s just one more thing that I can do, that my police department can do, to decrease this heroin epidemic,” he said.