OCEAN COUNTY – On the evening of May 6, 1937, hundreds if not thousands of spectators gathered at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst to watch the docking of the LZ-129 Hindenburg, an 803-foot-long airship that offered the most luxurious air travel the world had ever seen.

OCEAN COUNTY – On the evening of May 6, 1937, hundreds if not thousands of spectators gathered at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst to watch the docking of the LZ-129 Hindenburg, an 803-foot-long airship that offered the most luxurious air travel the world had ever seen.

At the time, the railroad ran special excursion trains from Jersey City to watch the airships dock, said Kevin Pace, a trustee and the immediate past president of the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society.

“Lakehurst was the airship capital of the world, and watching an airship dock was a very big thing of interest, like in modern day when people would go to Cape Canaveral for a launch. There would be concessions stands set up, and huge crowds. It was a big event,” he said.

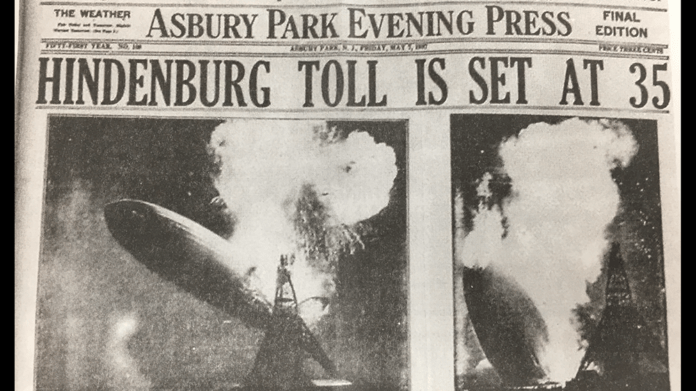

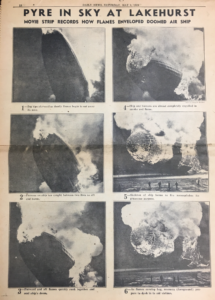

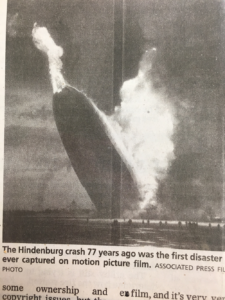

Many have seen the footage from that night, which was the first disaster captured on motion picture film: as it maneuvered, the Hindenburg’s forward and aft engines idled while the forward landing line was lowered and water ballast was dropped to lighten the craft.

The line descended toward members of the ground crew – sailors and civilians employed under the federal Works Progress Administration, who waited to connect it to mooring cables. There were 139 civilians being paid $1 an hour to help the Navy crews with the landing lines.

At 7:25 p.m. the Hindenburg caught fire and quickly became engulfed in flames. Eyewitnesses said that the tail section went down and the nose went up as the flames consumed the gas. Fire rushed out of the airship’s nose like a blowtorch. The airship burst into flames and crashed to the ground within 70 seconds.

The engines were still idling as the front passengers and crew members were jumping from the Hindenburg, some 200-300 feet above the ground. Others simply fell through the burned airship.

The Hindenburg had room for 70 passengers, but it was only carrying 36 during the crash. Of those, 13 died along with 22 of the 61 crew members, plus one person on the ground. Its commander, Captain Max Pruss, survived.

Director of Ocean County Business Development and Tourism Dana Lancellotti said that when she holds out-of-town promotional events, they promote the historical event and “people make a beeline for our table, and the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society brochure is very popular.”

“We feature the airship on our website, and we promote the anniversary as part of our tourism promotion,” Lancellotti said. “It’s an interesting part of our history and not your typical type of tourism event.”

That’s true, said Pace. There is still a lot of interest in the event, and while the public isn’t allowed to gather at the site because of security concerns at the air base, that’s not to say the tragedy has been forgotten.

An annual wreath-laying memorial ceremony is planned for May 6 for dignitaries, military personnel and others who had registered for the service.

A sold-out 80th Anniversary Memorial Dinner is planned for the Clarion Hotel in Toms River for May 5 when 220 attendees will hear two people who flew on the Hindenburg in past flights as featured speakers.

On April 30, a PowerPoint program presented by the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society, “Remembering The Hindenburg 80 Years Later” is planned for Jakes Branch County Park, along with the rededication of a 20-foot mural of the Hindenburg that had previously hung in the McDonald’s in Lakehurst. The artist, Cathleen Englesen, will be on hand to discuss the mural, which is permanently housed in the nature center there.

The Heritage Center Museum is located on the base and has an airship display spanning the years of 1921 to 1962, said Pace, who is the curator of the airship display. Approximately 4,500 visitors toured the museum last year.

Some tourists visit the museum and base because of the Hindenburg disaster, but many come to see the museum’s large display on Vietnam POWs, he said.

“We have a lot of Vietnam veterans passing through, and pilots, flight crews and others who were associated with Lakehurst and are taking a sentimental look back,” he said. “Some tell us stories. They bring and donate artifacts, and because of that we have a tremendous amount of model ships and aircraft.”

Tours are available of the base and the Heritage Center Museum by registering two weeks in advance at nlhs.com, and they are conducted on the second Saturday of the month in the winter and on the second and fourth Saturdays during the summer.

The Ocean County Historical Society in Toms River has a permanent Hindenburg display, including artifacts from the airship and more. Airships, although not the Hindenburg, have graced the town of Lakehurst in various ways, helping to forge the town’s identity. An airship insignia appears on signs welcoming people to the borough of Lakehurst. It also appears on the sides of Lakehurst police cars, letterheads, and – before the paint wore off and cell phone antennas were installed – on the Lakehurst water tower.

Also, there used to be an Airship Tavern in Lakehurst. Airship Storage is still in business, and a Lakehurst motel still uses the image of an airship of their sign.

The only nod to the Hindenburg disaster were uniform patches once used by the Lakehurst volunteer fire department that showed the airship in flames since they responded to the fire 80 years ago, Pace said.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the airships are also a tourism destination.

“In Friedrichshafen, Germany there is a big tourist attraction. It’s major. That’s where airship tourism is. The Zeppelin Company is headquartered there and it’s still in existence. It never closed,” Pace said.

Airship aficionados visit the Zeppelin Museum on the top floor of the Friedrichshafen Town Hall where they have built a replica of sections of the Hindenburg, including passenger compartments and the dining room. The museum also has some remains of the Hindenburg – the nose cone, a propeller, engine and pieces of scorched girders.

There were hundreds of dirigibles taking off and landing at Lakehurst, starting in 1923 with American Navy airships. The first passenger-carrying airship was the Graf Zeppelin, the Hindenburg’s sister ship, which landed in Lakehurst several times between 1928-1930. Then there was a six year gap until the 10 landings of the Hindenburg in 1936. The 1937 disaster was the first passenger-carrying flight of that year, and a total of 18 were scheduled, Pace said.

“It’s a business that’s fading away. There are only one or two companies in the world that still make dirigibles,” Pace said. “Zeppelin is strictly a branding company. Zeppelins are only built by the Zeppelin company.”

The rigid frame airships were the pride of the German aircraft industry. Travel in Zeppelins had begun in 1928 and was trendy and expensive: a one-way ticket on the Hindenburg cost about the same as the average annual salary of a German at the time. The other regular Zeppelin route was between Frankfurt and Rio de Janeiro, which cost even more.

According to Airships Magazine, the Hindenburg cruised at about 80 miles per hour, much faster than ships at sea without the discomfort of seasickness, according to promotional material.

Travel time between Lakehurst and the European terminal at Frankfurt-Am-Mein averaged 52 hours eastbound and 65 hours westbound, propelled by four 1,000 horsepower Daimler-Benz diesel engines.

The Hindenburg was gigantic, some 800 feet long and 10 stories high with the swastikas of Hitler’s Germany painted on the tail fins. Seven million cubic feet of highly flammable hydrogen was divided into 16 huge lifting cells above passengers’ heads that was used to lift the airship.

The airship was supposed to be the first of 40 to 50 Zeppelins to be built by 1947, but its destruction marked the end of “silver whales” in commercial aviation and was the symbolic finale of an era.