PINE BARRENS – William “Bill” Lewis, 50, served as a Marine, studied hard at night to earn a degree with top honors, and works for the federal government. On top of all that, he’s authored four books, produced a documentary film, and delivered guest lectures on several occasions.

Lewis also just happens to be a third-generation Piney, a fact that might strike some as inconsistent with their image of a people quite proud of their deep-rooted lineage.

The term “Piney” often conjures up images of backwoods stereotypes or folklore characters. Lewis considers the word an unmistakable slur and has made it his mission to reclaim the narrative of the Piney identity.

“We know with a stereotype there’s little to no truth,” said Lewis. “We’re just labeling people because they’re different, and we don’t understand them.”

The spark for Lewis’ first book, “New Jersey’s Lost Piney Culture,” ignited during a seemingly ordinary encounter. An avid birder, Lewis was hiking in Florida when he met a couple from Indiana. The gentleman, sporting a Wharton State Forest hat, asked Lewis if he’d ever heard of the Pine Barrens.

Lewis explained that he was from the Pine Barrens and was surprised to hear the couple had just visited the area. They became interested in it after reading “The Pine Barrens,” a book written by John McPhee in 1967, a staff writer for The New Yorker.

“I’d never read the book, but my curiosity was piqued, and I picked up a copy,” said Lewis. “In my opinion, it’s what saved the Pinelands. It galvanized the environmental movement and made it a national preserve along with Governor Byrne.”

While some of the book’s details rang familiar, others hit Lewis to his core. McPhee said the classic example of a Piney was someone who pulled pinecones and red sphagnum moss. Lewis recalled his close family members doing the same and came up with the conclusion that his family were Pineys.

“And then he said that Pineys was a derogatory word,” Lewis related. “And referred to backward people and incestual and immoral people.”

Lewis knew at the point that it was time for someone who lived the Piney culture to set the record straight.

The History Of The Pineys

In “New Jersey’s Lost Piney Culture,” Lewis identifies ten types of Pineys – all of whom have enjoyed the vast land known as the Pine Barrens. His research revealed that the Pine Barrens comprises 1.1 million acres in 56 municipalities.

As far as Lewis is concerned, one doesn’t have to be from the Pine Barrens to earn the Piney distinction. He gave the example of a woman who moved from Staten Island as worthy of being called a Piney – because of her sheer love for the land.

“I am a different Piney than my grandfather was,” Lewis added. “He couldn’t read or write.”

“I’m college educated, but that doesn’t mean I’m smarter than he was,” continued Lewis. “He had a different knowledge set than I do.”

The origins of the term “Piney” trace back to the Pine Barrens, where early inhabitants forged a way of life deeply intertwined with its beautiful landscape. For generations, Pineys fostered a spirit of self-reliance and community – living off government-owned land.

Lewis described his grandfather’s generation as pioneers and painted a picture of a community adapting to the seasons and opportunities available to them.

“Their routines shifted throughout the year. They’d pick blueberries in the summer and participate in the cranberry harvest come fall – both staples of Piney history,” said Lewis. But that wasn’t all. Year-round, they’d collect dry flowers, a tradition that stretched all the way down to Tuckerton.

Many of the people Lewis interviewed for his book recalled meticulously collecting “pine balls,” as they were called, specifically from pygmy pines. Pinecones and dried flowers served a decorative purpose, fueling a thriving industry until its decline in the 1990s.

Plastic flowers took the place of dried natural blooms – and pinecones were suddenly imported from overseas.

Lewis reminisced about his childhood and recalled the excitement of knowing there was always something to harvest and make some money. He credited his strong work ethic to the days he and his little sister bundled up to collect pine balls in Warren Grove. People dressed in their Sunday finest stared at them when they stopped in a diner to warm up and get special treats.

“I consider Pineys to be farmers without owning the land,” explained Lewis. “They were farming with different types of plants in the Pine Barrens.”

However, a shift came with the establishment of the Pinelands National Reserve. Public lands had always been associated with rules against removing anything from them. What had been somewhat lax enforcement changed. What was once considered sustainable harvesting – collecting pinecones and participating in the dry flower trade – was absolutely against the rules.

Authorities cracked down, impounding vehicles and issuing fines. A way of life passed down through generations became an unexpected source of conflict.

Meanwhile, the Pineys’ struggle with misconceptions dates far back in history. In the early 20th century, acting New Jersey Governor James F. Fielder ran for office advocating for the segregation and sterilization of Pineys. His stance was based on a flawed eugenics study conducted by Dr. Henry Goddard.

“It was his findings with a young Piney girl that really started the eugenics movement,” said Lewis. “It was the idea that she was feebleminded, and it was something that was bred and went up and down the family tree.”

More On The Pine Barrens

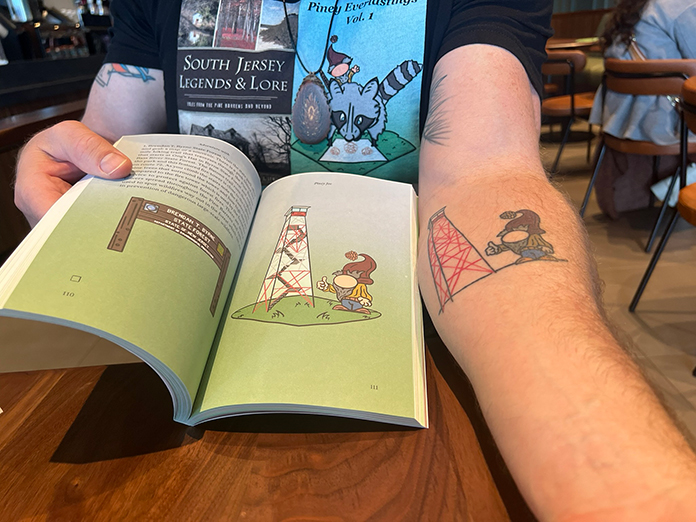

A world traveler who truly feels there’s no place like home, Lewis speaks passionately about the Pine Barrens. He’s an expert on the region’s flora, the hidden paths leading to tranquility, and even its local legends. His latest book, “South Jersey Legends & Lore,” explores both the well-known Jersey Devil and lesser-known stories like John Bacon’s tale, highlighting the Pine Barrens’ role in the American Revolution.

For younger audiences, Lewis crafted “Adventure With Piney Joe,” which takes children on a journey blending history with folklore, fostering an appreciation for the area’s people and rich heritage. Lewis has also designed a coloring book called “Piney Everlasting, Volume 1.”

The documentary, “The Reluctant Piney,” offers a glimpse into the lives of other Piney community members, further enriching the understanding of this resilient group.

“I call them reluctant because they’re reluctant to leave the woods,” Lewis explained. “They’re reluctant to get a 40-hour workweek – reluctant to have a boss.”

“They were all their own individual bosses,” continued Lewis. “Whatever they did in the woods that day, that’s the amount of money they would come home with. Progress kept coming along and pushing them out of the woods.”

Lewis’s books are available on Amazon. For those interested in learning more, his Facebook page, Piney Tribe, boasts over 11,000 followers and offers daily content about the Pine Barrens and its people.