BRICK – Holocaust survivor Maud Peper and her younger sister, Rita, spent most of World War II hidden away on a farm in the Netherlands, separated from their parents and forced to adopt new names and new identities while being concealed from the Nazis by the Dutch resistance.

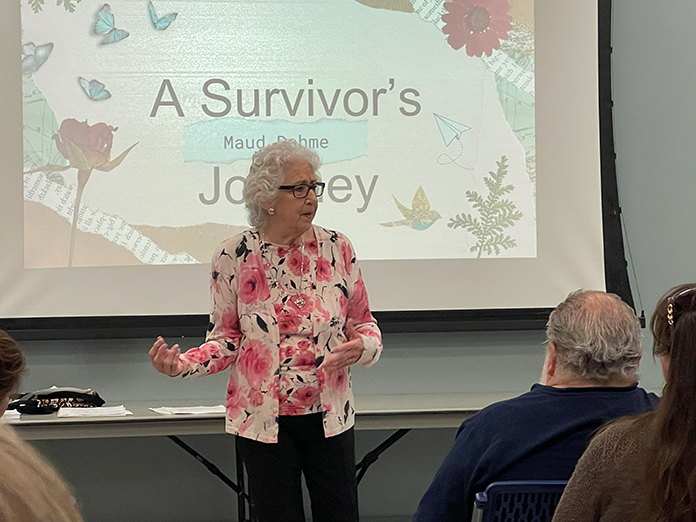

The girls were just 6 and 4 years old respectively, and during a recent presentation at the Brick Library, Maud Dahme (her married name) said she was forced to grow up quickly.

Born in Amersfoort, Holland in 1936, Dahme recalled her childhood and how life began to change for the Jewish residents after Hitler came to power in Germany, especially after Kristallnacht (or the Night of Broken Glass), named for the shards of broken glass that littered the streets after the Nazis broke the windows of Jewish-owned businesses.

“Every Jewish person had to register, they had a list, and anyone over 6 had to wear a yellow star,” she said. “Every Jewish person who worked in government, including teachers, was fired. Jewish children were not allowed to go to public school.”

Signs designed to isolate the Jewish population started to appear that forbade them from using the parks, using public transportation, going to the movies, eating in restaurants, socializing with non-Jews and more.

“Life became very difficult,” Dahme said. “We had to be very careful.”

In May 1942, their rabbi summoned his congregation to the synagogue to read a letter that was written by the German command.

“The letter said there was wonderful news: the Germans were going to take the Jewish population away from the war scene, that we should bring one suitcase or backpack and board trains that would take us east,” she said.

Afterwards, the Peper family, trying to get more information, secretly visited with their gentile friend, who was the deputy mayor, and they noticed the same letter from the German command on his desk.

The deputy mayor had been working with the Dutch resistance who had been traveling all over the Netherlands asking Christian families if they would be willing to take in Jewish children.

“Children are our first priority,” he said. “I have an address for your children. I can’t tell you who they are, I can’t tell you where they live, the only thing I can tell you is they live on a farm, and we must have your answer by tomorrow morning.”

Their answer was yes, Dahme said, so the next day, the couple had to surrender their 4- and 6-year-old daughters to the Dutch resistance, not knowing if they would ever see their children again.

The sisters were brought to a local home and were woken up in the middle of the night and spirited through the woods to a train station in another town. They traveled to an area of the Netherlands inhabited by poor and deeply religious Christian farm families. German soldiers were everywhere, she said.

The girls, who went by the new names of Margie and Rika Spronk, were fortunate to end up spending the next three years with a kind, older, childless couple who introduced the sisters as their nieces whose city home had been destroyed by bombs.

After the liberation in April 1945, the sisters were with their “Aunt” in the farm’s pumphouse when a man and a woman showed up in the doorway. It was their parents, who had survived the war by hiding in the Amersfoort attic of a friend’s car dealership. Neither of the girls recognized them.

After a few days, Dahme recalled agreeing to go home with the couple, “but if we don’t like you we’re coming back and staying with Aunt.”

There were 140,000 Jews living in the Netherlands before Germany invaded in May 1940, including some 15,000 who had fled Germany.

By the summer of 1943, 107,000 Jews had been transported to the extermination camps, according to the World Holocaust Remembrance Center. Only 5,000 returned after the war. More than 75 percent of Dutch Jews perished in the Holocaust, including most of her uncles, aunts and cousins.

Dahme said that 24,000 Dutch Jews went into hiding and 16,000 of those were not discovered..

She has dedicated her life to educating students, teachers and other groups about the Holocaust and ensuring it is not forgotten by speaking about her experiences as a young child in hiding and about the bravery of the resistance fighters.

Dahme began her presentation by reading a passage from “Facing Memories: Silent No More,” by Holocaust educator and survivor Dr. Robert Krell, who said child survivors lived in silence after the war because silence served them well while in hiding.

“Survival so often depended on not being noticed, being inconspicuous on the ability to suppress tears and ignore pain,” Krell wrote.

“Grief was borne in silence, and so was rage. Silence is the language of the child survivor. We might have talked after the war, but adults persuaded us to get on with life and forget the past. Adults who themselves had survived, and suffered so much, inadvertently diminished the experiences of the children. In the aftermath of that silence…what needed saying was not said.”

This was true for Dahme, she said, and after the war when the sisters were reunited with their parents, they never asked their daughters about the three years they spent apart.

The family emigrated to the United States in 1950, but Dahme did not speak about her wartime experience until 1981 after a Holocaust denier criticized a program aired by 60 Minutes.

“I’m so grateful for the people who risked their lives to save us,” said Dahme, who has four children, nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

“Hitler did not succeed with our family tree,” she said. “Many branches were broken, but there are many new branches and blossoms.”