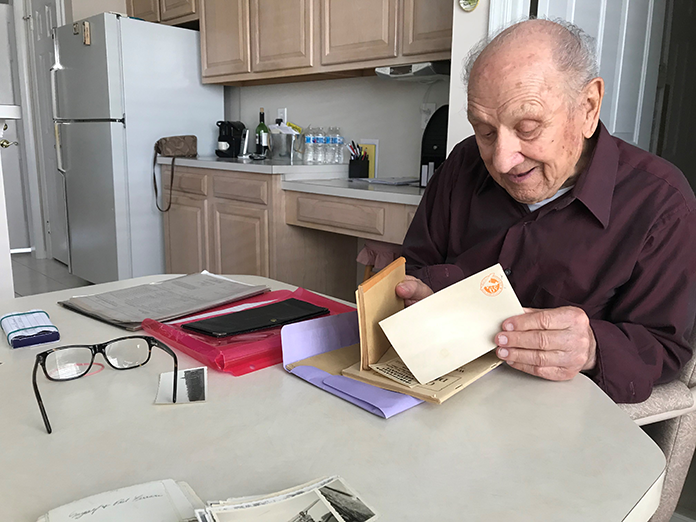

BERKELEY – Joseph Finamore has a few items decorating his house that suggest his Army service, but you don’t notice them right away. When he pulls out a collection of photographs and documents of his time in World War II, he recalls 70-year-old memories like they were yesterday. Dates, deployments, even the spelling of his fellow soldiers’ names spring to mind. And the stories! Anything that happened to him would be considered unrealistic if you saw it in a movie.

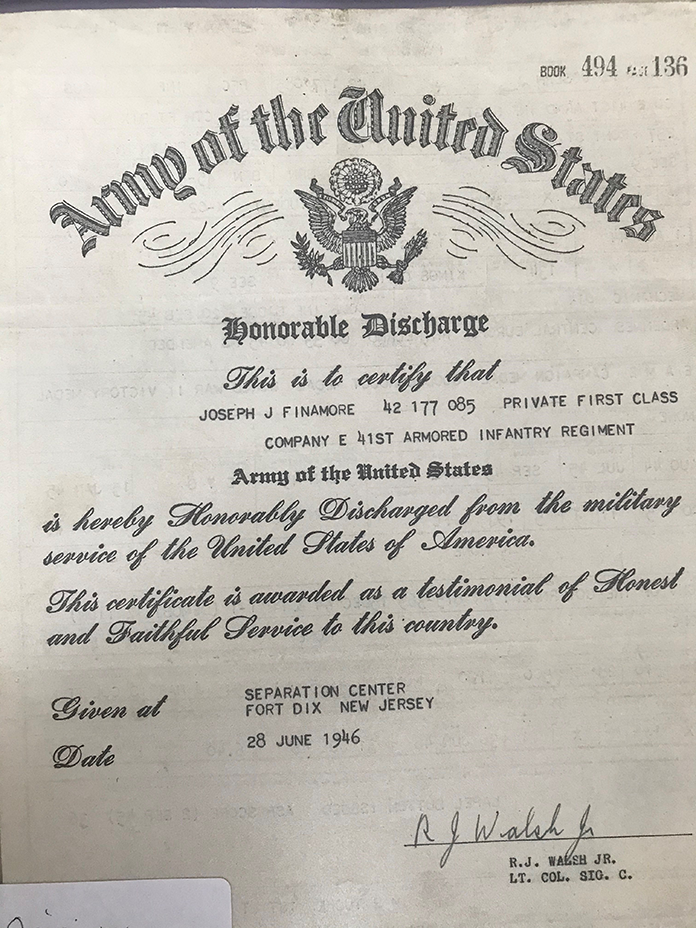

Army Private 1st Class Joseph Finamore was drafted into the army in 1944 and was honorably discharged in 1946. He was 15 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

He was born on June 6, a date that would later be called D-Day. Originally from Brooklyn, he lived near the bridge for most of his life. He now lives in Sonata Bay with his wife, Priscilla.

He spent 14 weeks of training in Little Rock and then he was shipped over to La Havre, France. At one point, there was a plan for him to serve in the Pacific Theater, but that didn’t happen. As a member of the 2nd Armor Division, he went through many countries in the European Theater of Operations.

It wasn’t lost on him that he was serving as a replacement for other soldiers in the division.

But that’s not something that an 18-year-old man dwells on. He never really realized the danger until later in life. After all, other family members had already served in the military.

“When you’re 18 years old, anything means nothing to you,” he said. “You see why you’re a replacement – the guys you are replacing are gone, either dead or wounded.”

They were the first American division in Berlin. He saw Belgium, Germany, Holland and other locations over his two years.

“I say ‘only two years’ because some people were in a lot longer than that,” he said.

He didn’t take any of the photos he now has in his possession. They were given to him by soldiers he served with that he kept in touch with. He had more, but his dog ate them.

Some pictures show destroyed buildings, but it’s not all bleak. Some show him relaxing with fellow soldiers or locals. He got to know a family in Schwarzenfeld, Germany, and there’s a photo of him with one of the young children. He had a photo taken with Charlie Strahm, another soldier stationed in his division who by coincidence was from his neighborhood. He was the youngest guy in the company since he just got drafted.

One is a line of military vehicles called halftracks where he was stationed, which just so happened to be the 1945 Potsdam Conference, where the leaders of the Allied Powers – Truman, Churchill, and Stalin – met to decide how to deal with Germany’s fate after their surrender. His division had an inspection from the new President Truman.

Moments like this wind up in history books. But there are a lot of stories that soldiers bring home that you’ll never see in a book, and they might never tell anyone. Fortunately, he sat down with The Berkeley Times to share some of these stories.

At night, the soldiers would have to find a place to bunk down. Some officers had their troops dig foxholes. They didn’t want them staying in the abandoned houses because they could be a target, or the abandoned houses could be booby trapped. One superior officer allowed them to stay in the houses and something unbelievable occurred.

He happened to be sharing the house with Dr. Dworkin who also, coincidentally, was from Brooklyn. In the morning they heard a knock at the door. Finamore took his rifle and went down to answer it. Standing before him was a Nazi soldier who started speaking German to him.

Dr. Dworkin, who was Jewish, knew a little German, so Finamore went to fetch him. Dworkin was able to translate enough: “This is my house,” the Nazi said. “I want to know what happened to my family.”

Finamore and Dworkin didn’t know, but they left the man to his home and moved on. Amazingly, these three armed soldiers from different sides didn’t resort to any violence.

In another crazy story, General Eisenhower gave his division orders to go to the Elbe River to a German town called Magdeburg. They were fighting inside the city but then they were told to leave and wait in a field so bombers could hit the city.

“We crossed the Elbe even though we weren’t supposed to. When we go into town, people are firing at us.”

They couldn’t see where the shots were coming from. It was somewhere in the ruins. When they finally got a fix on them it turned out to be Hitler Youth.

“We see kids in white shirts and blue pants. We didn’t know who was shooting at us. They didn’t know what was going on. They were just told to fire at us,” he said.

A lot of the Germans would surrender to them because if they surrendered to the Russians they’d be executed, he said.

He keeps a box of fascinating artifacts like his ration card and his pay book – items that most people didn’t keep. Of course, he still has his Bronze Star, Selective Service and Honorable Discharge papers.

He even has his late brother’s medals and belongings. He has his father’s Heroic or Meritorious Achievement Medal, but unfortunately he doesn’t know the story of how his father earned it.

Upon his discharge, he was given $100 cash and a check for $200 later. He still has a certificate the Army gave him to pay for the ride home because he never used it. Even that wound up being a story. Another officer took him home but his car broke down. They had to push it to a gas station and they needed $35 to fix the generator.

“After the war, it was like Christmas every day. It was so good,” he said. He became an ironworker and even worked on the Brooklyn Bridge that he grew up near.

Now 95, he is the father of three and his wife, Priscilla, has two.

His nation remembers him, too. His name is on the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C.