BERKELEY – A small, cramped space. Rationed food and water. Not much to do but sit and wait.

But it beat being outside in the radiation.

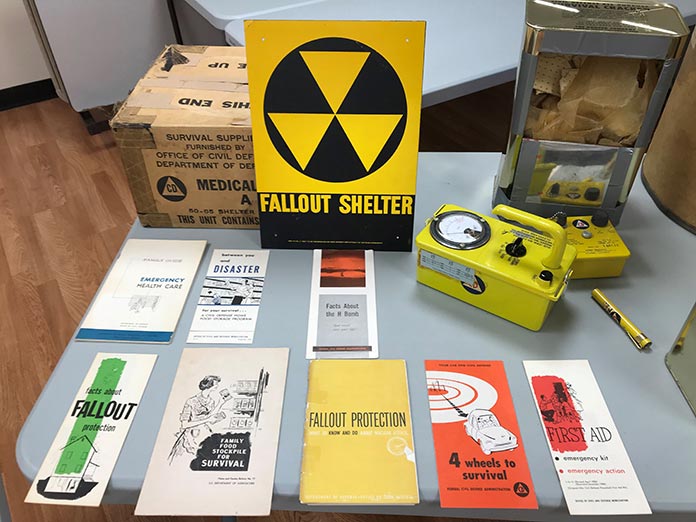

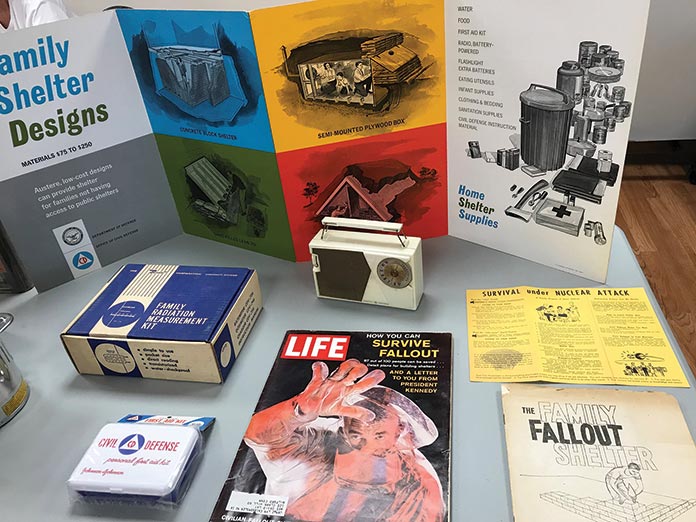

The Berkeley Township Historical Society hosted a speaker who brought actual items from fallout shelters and explained the mindset of people who were looking at escalating tensions between the U.S. and Russia.

Jeff Brown, a history teacher at Southern Regional, said his students respond really well to the artifacts he brings in. The items impress the reality of it upon the students. Looking at a “Time” magazine cover lets kids know what people were thinking back then. Showing the rations people were supposed to eat in a shelter drove home the era for kids who were born 40-50 years later.

The people at the historical society were just as intrigued. Some of them shared stories of the Cold War era and the things they were told.

Brown touched on the politics behind why these fallout shelters were built. Nelson Rockefeller, who was governor of New York, met with President Kennedy to urge him to endorse fallout shelters. JFK pushed Congress for public shelters, which his friends criticized as ‘a great way to save Republicans,’ because that’s who was living in the suburbs and rural areas – and to a degree still are.

Brown briefly explained why an atomic weapon creates a mushroom cloud, what the radiation does, and why it’s so dangerous. With this as the backdrop, the audience had questions if a fallout shelter would actually work.

Even if it didn’t, the point was to have a plan, he said. This was the federal government telling people that there is a plan for the worst case scenario, whether that plan worked or not. Part of this was to calm the public.

The consensus was that it might slow the impact of radiation, but it’s not going to make you 100% safe.

“So much was theoretical,” Brown said, “based on the low-yield weapons used in Japan.”

The expectation was that you would stay in the shelter for about two weeks. But what did that two weeks look like?

Brown showed some items that would be stored in a shelter. He had cans of water that were still full, never opened. They were still drinkable. The public shelters had water rationed for one quart per person per day. Between this and the low calorie content of the food stashed away, you would end those two weeks dehydrated and malnourished. And then you would open the door to a brave new world where the radiation had hopefully disappeared after two weeks.

A pack of saltines from an opened ration was offered to the crowd and a few brave people took them. The verdict? “It’s what despair tastes like.” They quickly downed some snacks that were provided by Historical Society members – not from the rations – to get the taste out of their mouths.

Speaking of snacks, there was also a candy in the shelters. These sweetened bites looked like cereal and they also served as a carbohydrate supplement to keep your weight up while self-incarcerating. As it turns out, though, one of the food colorings used was the infamous red color that was later found to cause cancer.

The less said about the makeshift toilets, the better.

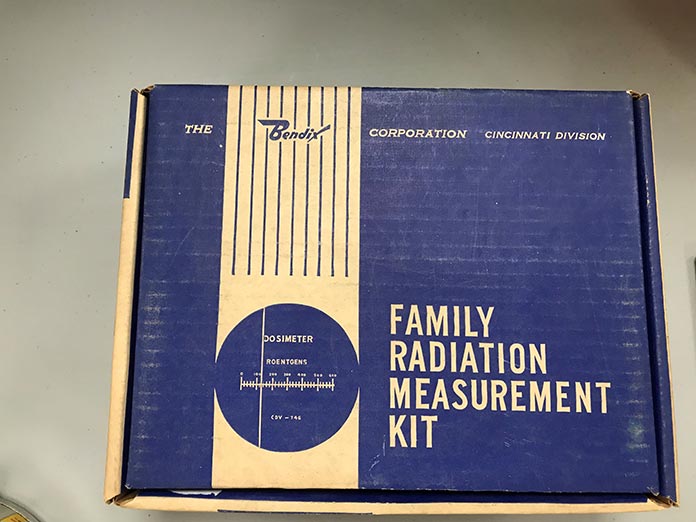

A battery-powered radio is something that is important to have in your house in case of emergency even today. A family radiation measurement kit is less likely to be in your home.

Some of the name brands on the products in the rations and on the equipment are companies still around today.

These public shelters were closed in the 1970s, but some might still remain, like hidden time capsules.

Brown said he knew of three public shelters that were located in Ocean County. The Ocean County Courthouse had one. Another was the BOMARC missile compound near the Joint Base. The third was Texas Tower 4, which was 85 miles off the coast of Long Beach Island. Its job was to spot enemy submarines. The tower was lost to a nor’easter in 1961; the 28 on board were lost because their Air Force superiors didn’t let them evacuate.

The public versions of these shelters were hidden away in buildings like schools, marked by the yellow and black radiation sign. He said one was even found when taking a bridge down. But people were expected to build them on their own property. Because these were not inspected or on any building plans, it’s unknown how many people actually built them. It’s believed that there were about 200,000 nationwide.

The cost to build one might be a bit steep, and you needed the property to do so, therefore it was believed that middle and upper class people were the ones doing this. There were even private companies you could hire to build them for you.

The shelters themselves were not very large, and there were not always a lot of supplies available, so what would you do if someone knocked on your door to use it? The question became “Is it love your neighbor or gun your neighbor?”

This was another reason that the total number of shelters is unknown. If you had one in your home, you might not want to make that known to everyone in case the entire street comes calling.

If the suburbs and rural areas were the places people could build them, why would they? What would be the threat level on the Jersey shore?

Ocean County would be a target-rich area, he said. There’s the Joint Base. There’s Oyster Creek. And we’re somewhat nestled between New York and Philadelphia.

There were far-reaching consequences of this era, Brown explained. The Civil Defense portion of the government that planned these would evolve over time to become the Federal Emergency Management Agency.