BRICK – Live-in rehabilitation centers are the wrong thing for opioid abusers because many insurance companies will only pay for a 14-day stay – and even those who will pay for a stay of up to 90 days – is not nearly long enough, said physician Dr. Christopher Johnson, who works as the chief medical officer for a national chain of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) centers.

“There is a higher chance they will die when they leave rehab because they’ve been off the drugs completely, and when they get out they take the same dose they were taking before,” he said during the opening of a new treatment center on Brick Boulevard last week.

Residential rehab can be effective for those who abuse alcohol and so-called “benzos” (anti-anxiety medication like Valium and Xanax), but opioid abusers need long-term treatment and medication, like suboxone (buprenorphine), naltrexone and methadone to make the cravings go away until the brain starts to work normally, he said.

“Then they can sit with a counselor and make sensible choices and benefit from counseling,” he said. If they don’t agree to counseling, they don’t get their medication at the center, he added.

Ocean Monmouth Care can treat 2,200 walk-in patients a day. The facility is part of Pinnacle Treatment Centers, a private, for-profit company with 12 centers in New Jersey.

The combination of counseling and daily medication has been effective in treating opioid addicts, who are usually in their late 20s or early 30s with an even mix of males and females, Johnson said.

The outpatient treatment centers offer accountability and support, and people are able to get help in their own community, he said.

Johnson said that about 92 percent of their patients are still coming in for their daily medication after a year, as opposed to those who have been in residential rehab, where about 80 percent have relapsed after a year, he said.

“We don’t kick them out for not getting off drugs. They have ups and downs,” the doctor said.

During early recovery, patients typically have low self-esteem, but after a year they get over that hump and life starts to get better, he said.

“After a year, the outpatients are using less, they’re getting counseling, they’re trying. They’re in treatment, they come in here because they don’t want to live that lifestyle anymore,” he said.

The cost of treatment averages about $90 a week, but only an estimated ten percent of drug abusers seek help, he said.

The Murphy administration supports the use of medication to treat substance abuse and is pushing to train family physicians to take an eight-hour course on how to use the drugs, said NJ Health commissioner Dr. Shereef Einahal, who attended the opening.

Einahal said that Ocean County is one of the most devastated areas in the state in terms of overdoses and resulting deaths.

“There have already been over 400 deaths in 2019 in New Jersey and 30 in Ocean County,” said the health commissioner.

“We license centers like these because it’s safe treatment, and they have the right staffing and training,” he said. “We need clinics like these and other mental health facilities that can reduce barriers and treat addiction.”

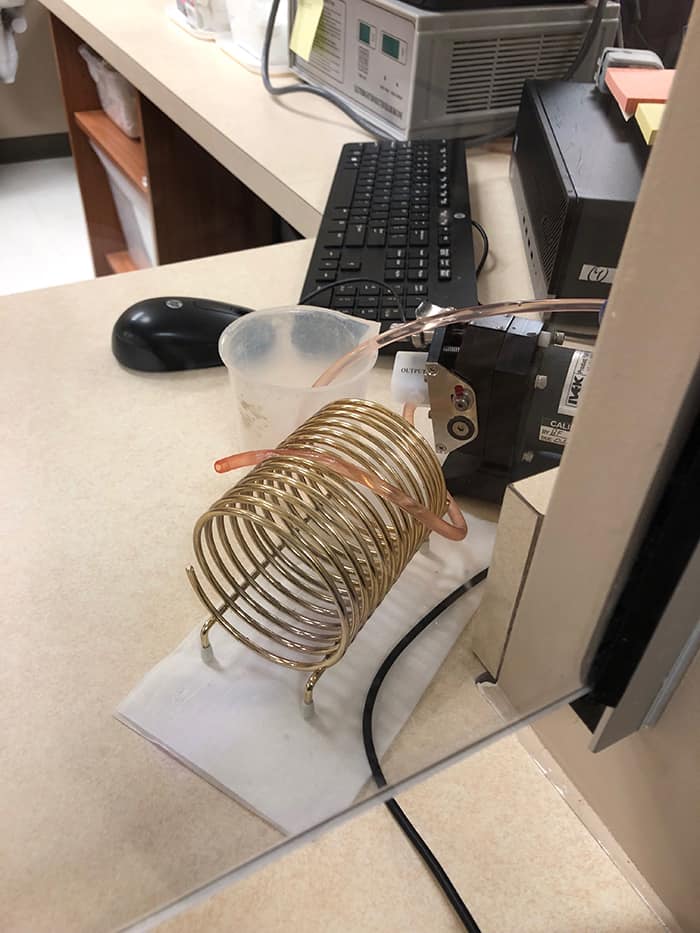

Opioid abusers are treated six days a week at the outpatient clinic. They enter the building and check-in on a computer screen. Then they are called to one of about a dozen windows, where a nurse gives them a suboxone pill, which they put under their tongue, take a seat within view of the nurse and sit on their hands until the pill has dissolved.

If methadone is warranted, the patient gets the measured liquid in a cup at the window and drinks it in front of the nurse.

On the seventh day when the center is closed they get a pill to take at home, Dr. Johnson said. After two years, if they are doing well, they can bring the pills home and come in for monthly checkups, he said.

Suboxone can be continued long-term, but most people get weaned off methadone, he said.

Addiction is a chronic, treatable brain disease brought on by a combination of environment and genetics, and addiction can result when stress is combined with exposure to an opioid.

“It’s not an opioid crisis, it’s a behavioral health crisis,” Johnson said. “People have emotional and mental problems – we’re not talking about people who are schizophrenic or bipolar.”

Most drug abusers get addicted from a friend, who offers them the drug for the first time. With recent limitations placed on doctors, there are fewer prescription opioids, like oxycontin, out on the street now, which can sell for about $60 for a 30 milligram pill on the black market, Dr. Johnson said.

“And the oxy might not be oxy, it could be fentanyl, which is much more potent, and it is showing up in Xanax, amphetamines, cocaine, and in bags of heroin – and the amount varies,” the doctor explained. “And it’s incredibly lethal, you can’t tell by looking at it. That’s why the [overdose] death rate is so high.”

With doctors now prescribing fewer opioids after learning about patient overdoses, abusers are moving back towards using heroin, and there has been an upswing in methamphetamine usage because of the fentanyl risk, he said.

“Medication assisted treatment saves lives,” said Dr. Johnson.